Christian History and the Catholic Church – Part 3

It is a testament to the superintendence of God protecting and sustaining the church, his bride, that she has survived nearly two millennia of heresies, persecutions, divisions, and direct attacks aimed at consigning her to the dustbin of history. And that the inspired Scriptures have survived as well, giving us a reliable record of what Jesus and his trusted apostles did and taught in first century Palestine.

It is also a testament to the faithfulness of the church fathers who diligently contended for the true faith in the early centuries against rampant heresy. Irenaeus, bishop of Lyons, was one of those faithful men. Last time I introduced a statement made by Irenaeus in Book 3 of his multi-volume work Against Heresies, in order to dispute the Roman Catholic Church’s interpretation of it as supporting her claim to jurisdictional primacy over the entire Body of Christ. Today I continue with context and crucial details in Part 3 of my own multi-volume work, which I should have titled Against Roman Primacy.

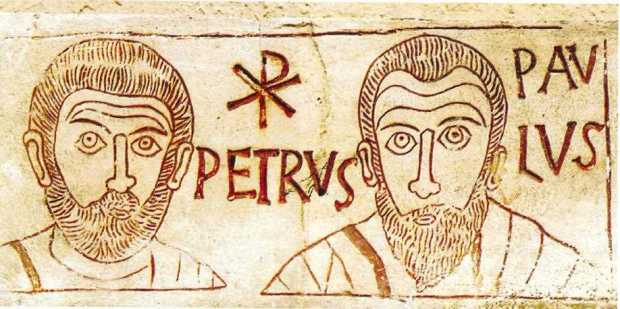

When Irenaeus singled out Rome to establish apostolic succession in refuting the heretics, it was not without good reason. The church at Rome held a preeminent position of honor and influence because of the labors and martyrdom there of “the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul,” and because as the seat of the empire it had a large population and a bustling tourism industry of sorts. Lots of people and pilgrims passed through it. Its centrality and political importance would later contribute to the Roman church succeeding in elevating itself as the central authority in Christendom, but that was still roughly two centuries away when Irenaeus wrote his treatise.

Rome’s political centrality also meant that it was a hub of heresy. Where better to propagate new teaching than where Peter and Paul taught and where multitudes were coming, going, and staying? The impetus for Irenaeus’ work seems to have been his experience at Rome when sent there as a presbyter of the church at Lyons “with letters of remonstrance against the rising pestilence of heresy.” In the introduction to Against Heresies the editors record this:

But he had the mortification of finding the Montanist heresy patronized by Eleutherus the Bishop of Rome; and there he met an old friend from the school of Polycarp, who had embraced the Valentinian heresy.

So not only was the “pestilence of heresy” rampant among the laity, it had infected the bishop of Rome himself. This wasn’t the first time and it wouldn’t be the last that the faithful from surrounding churches were commissioned to go to Rome for the purpose of correcting her errors. In this same book of Irenaeus’ Against Heresies where we find the pertinent passage, he mentions Polycarp, a disciple of the apostle John, and says, “He it was who, coming to Rome in the time of Anicetus [the bishop of Rome] caused many to turn away from the aforesaid heretics to the Church of God.” Tertullian (155 – 240 AD) and Hippolytus (170 – 235 AD) were two other church fathers who complained about bishops of Rome advancing heretical views.

With this background in mind, let’s look again at the passage that the Catholic Church cites as evidence of her supreme authority over Christ’s bride.

For it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church, on account of its pre-eminent authority,4 that is, the faithful everywhere, inasmuch as the apostolical tradition has been preserved continuously by those [faithful men] who exist everywhere.

As I said last time, the exact translation of this passage, from the Greek original to Latin to English, is disputed, which alone should render it inadmissible as evidence for Roman primacy. One group of translators into English has this footnote:

4 The Latin text of this difficult but important clause is, “Ad hanc enim ecclesiam propter potiorem principalitatem necesse est omnem convenire ecclesiam.” Both the text and meaning have here given rise to much discussion. It is impossible to say with certainty of what words in the Greek original “potiorem principalitatem” may be the translation. We are far from sure that the rendering given above is correct, but we have been unable to think of anything better.

The editors of the more recent English version add this:

A most extraordinary confession. It would be hard to find a worse; but take the following from a candid Roman Catholic, which is better and more literal: “For to this Church, on account of more potent principality, it is necessary that every Church (that is, those who are on every side faithful) resort; in which Church ever, by those who are on every side, has been preserved that tradition which is from the apostles.” (Berington and Kirk, vol. i. p. 252.)

The Berington and Kirk translation, from The Faith of Catholics published in 1885, definitely conveys a different meaning. It has “potent principality” for “pre-eminent authority,” “resort” instead of “agree,” and “those who are on every side” for “the faithful everywhere.”

So what is the best, most objective reading of this passage? Context and circumstances will determine that, and next time I’ll try and pull it all together and give what I believe Irenaeus is saying.

A whole lot of writing and no information.

I want my 5 minutes back!

😆

LikeLike

A whole lot of commenting and no good defense.

LikeLike

I read this and then took a nap . I hate to say this because I’ve always liked you, but you are boring. Stick to your church , believe in Jesus Christ like we all do and stop trying to justify your leaving the Church of your descendents. Amen. I’m done with this garbage unless I need a sleep aid in the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The truth makes your brother laugh and puts you to sleep. Interesting. The church of my descendants? I may be boring, but you on the other hand, never are.

LikeLike

Pingback: Christian History and the Catholic Church – Part 4 | a reasonable faith